This article is about addition and subtraction. They are foundational skills in mathematics, but they themselves depend upon a good number sense. This is the ability to recognise and understand the value of numbers. It’s also about the relationships between them. It’s about how they can be combined or separated.

With strong number sense, your child will more easily see how numbers fit together, making it simpler to add or subtract them. Solving addition or subtraction problems becomes more straightforward if your child has a good number sense.

Number bonds

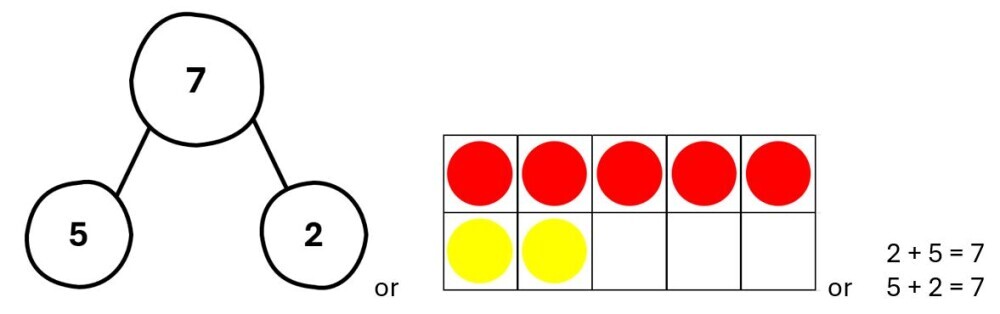

Number bonds are pairs of numbers that add together to make a particular total. You may hear about them from your child, especially bonds to ten. However, all numbers have bonds.

For example, one number bond to 7 is 5 + 2. This means that when a group of 5 is combined with a group of 2, it results in a larger group of 7.

As a number fact, it tells us that 2 and 5 added together make 7.

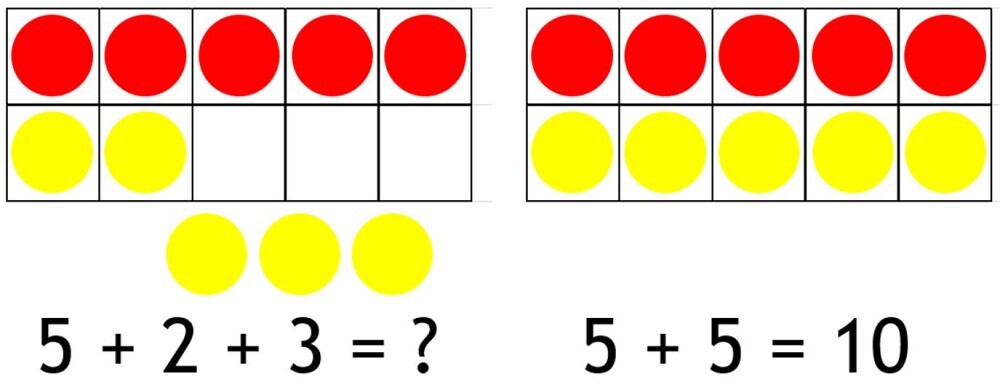

We can apply this knowledge to solving 7 + 3.

By splitting the 7 into 2 and 5, we can write 7 + 3 as (5 + 2) + 3. This can be re-written as 5 + (2 + 3).

When the 2 and 3 are added together, this gives us 5 + 5. Holding up both your hands you can see the total is 10.

This can be represented with coloured discs and a tens frame.

These are simplistic examples, and 7 + 3 = 10 is a number bond itself.

Seeing the bigger picture, this is a good example to show how maths knowledge is built up. One thing is built upon another, another is built upon it and so on.

We are encouraging an intuitive grasp of numbers that will allow for more efficient and, more importantly, flexible thinking.

Flexibility in Thinking

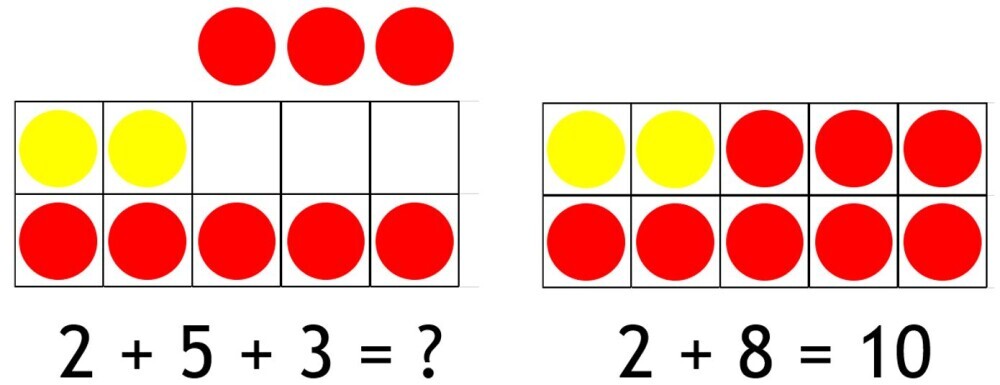

We can show this flexibility with our previous example of using 7 = 5 + 2 to help solve 7 + 3. We first arranged our calculation as (5 + 2) + 3, then as 5 + (2 + 3). When the 2 + 3 part was calculated we were left with 5 + 5.

We could have grouped them differently. Instead of putting the 2 and 3 together to give us 5 + 5, we could have put the 5 and 3 together instead. This would have resulted in 2 + (5 + 3) or 2 + 8 = 10. This is another bond to ten.

This knowledge ultimately gives a deeper understanding of how addition and subtraction work. As a result, flexibility and fluidity with numbers is encouraged. So too are quick mental calculations.

Number facts, including bonds within 20 and within 100

Bonds within 20 are a very important extension to the idea of bonds for numbers up to 10. They are an essential building block for understanding written methods of addition and subtraction.

Without rapid recall of these facts, written methods become a chore and resentment can set in.

Bonds within 100 are also important, but not knowing them quite so well does not have the same potential for causing problems as those bonds within 20.

There is a slight contradiction in that whilst knowing that 45 + 55 = 100 is not essential, knowing that 40 + 60 = 100 is. This is a place value related fact – related to the fact that 4 + 6 = 10.

A great way to attain recall of any number fact is through repeated exposure to them using concrete, pictorial and abstract representations. Playing games is a great way to provide this exposure.

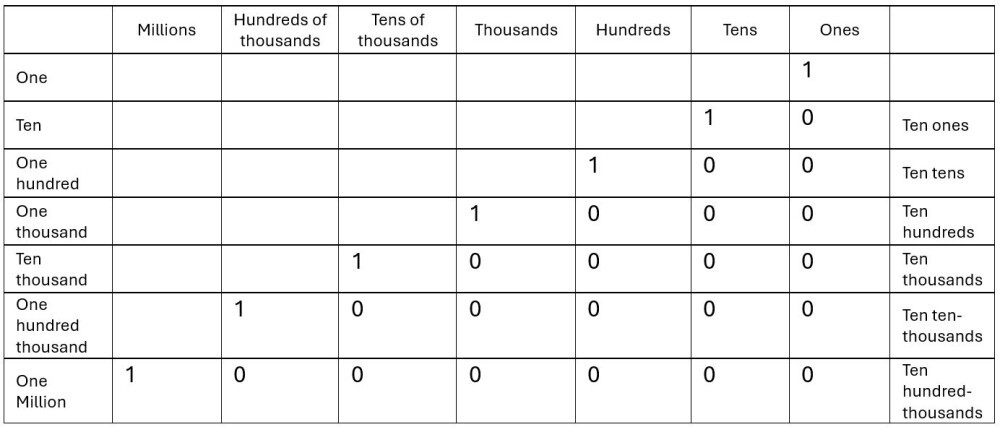

A Note on Place Value and Columns

We arrange our multi-digit numbers in columns. We generally don’t use column headings when we write out numbers. There is an assumption that the column or place we find each digit relative to gives us its place value and the overall value of the number.

For example, in the number 572:

- The digit 2 is in the Ones place; its value is two

- The digit 7 is in the Tens place; its value is seventy

- The digit 5 is in the Hundreds place; its value is five hundred

Thus, we read the number 572 as “five hundred and seventy-two.”

Multiplying and Dividing by Ten

In terms of positional value, let’s start with the Ones column. As we move to the left, the columns increase by a factor of ten. For example:

- A digit in the Tens column has a value ten times greater than if it were in the Ones column

- A digit in the Hundreds column has a value ten times greater than if it were in the Tens column

- A digit in the Thousands column has a value ten times greater than if it were in the Hundreds column

- And so it goes on…

This arrangement helps us see what happens when we multiply (and divide) by ten. When we multiply a number by 10, each digit shifts one place to the left, increasing its value tenfold.

For example:

If we multiply 3 by ten, the 3 moves from the Ones place to the Tens place. This creates a space in the Ones column, so we fill it with a zero. So, 3 x 10 = 30. This is why all multiples of ten have a zero in the Ones place.

Another example is the multiplication of 45 by 10. The 4 moves from the Tens place to the Hundreds place, and the 5 moves from the Ones place to the Tens place. Again, there is a space created in the Ones column. This must be filled with a zero. So, 45 x 10 = 450

When multiplying by ten, it is important not to just ‘add a zero’ to get the answer. This is a simplification which although reliable for whole numbers, does not work for decimals. The essential aspect is the movement of digits to the next column on the left each time a number is multiplied by ten.

Carrying Over and Exchanging

A different phenomenon occurs every time we accumulate a group of ten. Whenever we have accumulated a group of ten in one place value column, it ‘carries over’ to the next column on the left. Here’s how it works:

- Ones column: We start with single items. When we have accumulated 10 ones, they must be exchanged for a group of ten

- Tens column: A group of 10 ones is represented as 1 in the tens place with a zero in the ones place. Once we have accumulated 10 tens, we must exchange them for a group of 100

- Hundreds column: A group of 10 tens is represented as 1 in the Hundreds place. Once we have accumulated 10 hundreds, we must exchange them for a group of 1000… and so on…

Consolidation of addition and subtraction within one place value column only

It is important to consider that adding ten or groups of ten will not affect the ones column. Similarly, adding hundreds or groups of hundreds will affect neither the tens nor the ones column.

In this example, when 30 is added to 57, there are no spare ones in thirty. They are all locked up as three tens. As a result, the 7 ones in 57 are not affected. It is only the three tens of thirty that are added to the five tens of 57.

Addition and subtraction with increasingly large numbers using formal written methods

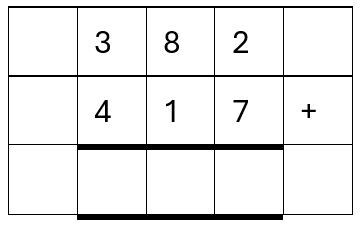

‘Formal written methods’ means column addition or subtraction. This is nothing more complicated than making sure the numbers you are calculating with are written out with their digits lined up in the correct columns.

Take the addition of 352 and 237. They should be lined up like this:

The 2 and the 7 represent the Ones and should appear in the same column together. 8 and 1 represent the Tens and should appear in the same column together. Finally, 3 and 4 represent the Hundreds – they too must appear in the same column together.

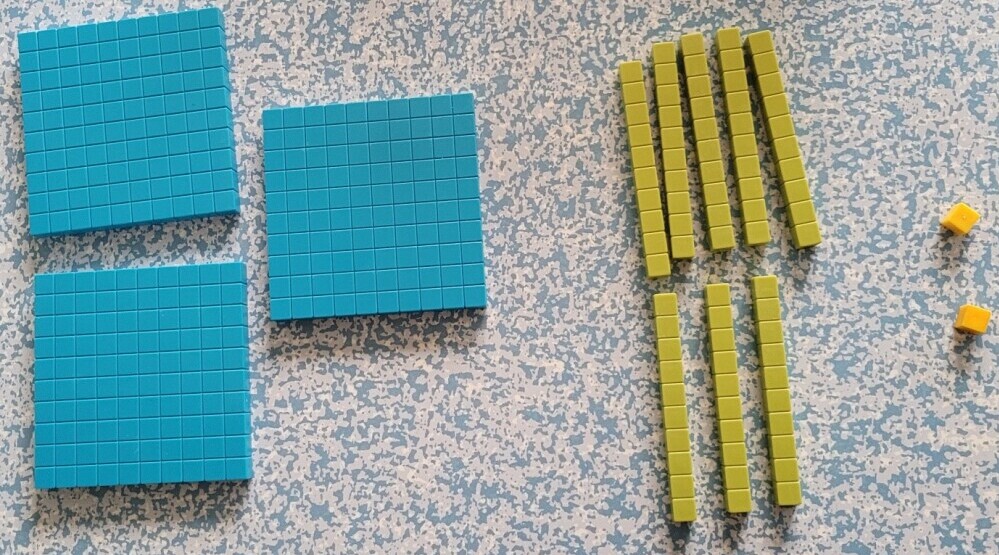

A question such as this one can be modelled using what is called ‘base ten equipment.’ Sets of ‘base ten equipment’ usually include ones, tens and hundreds. Some contain thousands. As a result, it is possible to model calculations with three-digit numbers.

For example, 382 is shown:

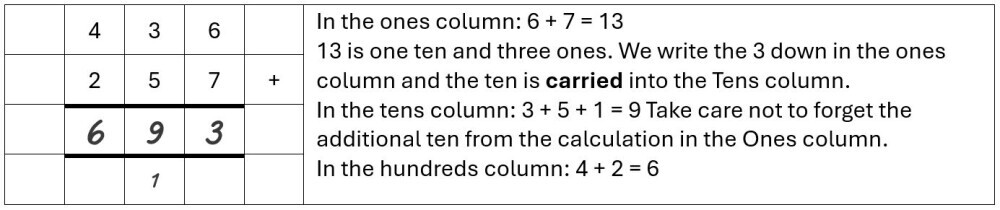

Once your child is secure in calculating with three-digit numbers, the column method extends your child’s ability to add and subtract increasingly large numbers using a small set of number facts. These are those number bonds and number facts up to twenty.

The column method is so powerful because it limits calculations to one column at a time. It is as if we are calculating only with single-digit numbers. Of course, when we are adding, as soon as the column total is ten or more, there is a knock-on effect into the column on the left.

Understanding what happens when we find ourselves with a group of ten or more is important. We call it carrying.

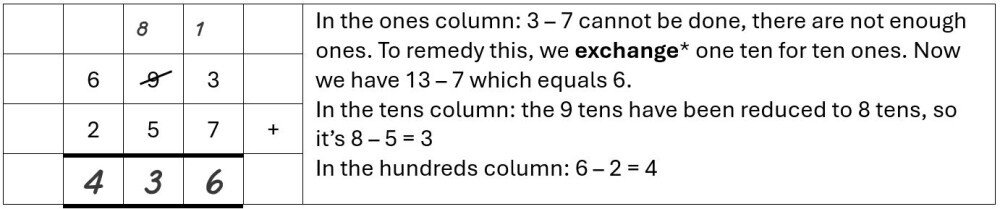

Similarly, when subtracting, if we find the digit being subtracted is bigger than the one on the top, we need to ‘knock next door, to get ten more.’ This is the decomposition of numbers. The ability to understand and carry out this task is important. It enables us to exchange from a bigger column on the left to a smaller one on the right.

*i.e. ‘knock next door, to get ten more’ or other variation

With all of this said, the introduction of the formal algorithms for addition and subtraction must done gradually. Knowing that what works in the Ones, Tens, and Hundreds columns works in any column is important.

Addition and subtraction with mental methods

We do mental maths in our heads, without using paper or a calculator.

To be good at it you need good number sense. Understanding numbers, especially how they are composed, will make it easier to solve problems.

Being good at mental maths can help your child think faster and make fewer mistakes. It makes them feel good about their math skills. They become more confident and independent.

There are many tricks and tips to help your child get better, but there is no substitute for practice. This is best done playing structured games using number facts.

In doing this, we are building upon number sense and developing automaticity of facts recall.

Problem solving with increasingly complex contexts. Applying number facts and place value knowledge

This is the bringing together of a range of skills. It utilises the skills of mental methods. It also applies the skills learnt in carrying out calculations using formal methods.

The key with problem solving is reading the question and working out which operation and method to use.

Questions may include numbers that are red herrings. These are numbers that are not of any use in solving the problem. The mnemonic RUCSAC gives us a great strategy to use:

Read the question

Understand the question

Choose the method

Solve the calculation

Answer the question – e.g., have you used the correct units?

Check your answer

Understanding the relationship between addition and subtraction. Using it to check calculations

This is a crucial piece of understanding. It builds on number sense, particularly the composition of numbers. For example, we have seen the relationship between 3, 4 and 7. This is, that 3 + 4 = 7 and 4 + 3 = 7.

These two addition calculations are basic number facts – bonds to 7. When they are put together in a part-part-whole model or with concrete objects, they can show us that 7 – 4 = 3 and 7 – 3 = 4.

This example shows us that addition is the putting together of quantities to make a larger quantity. Subtraction is about splitting a larger quantity into two or more smaller quantities.

This applies to all examples. Some, like 3 + 4 = 7 are number facts. Their knowledge and understanding make life easier when calculating with bigger numbers. For example, in the same way, 353 + 236 = 589 can be reversed as 589 – 236 = 353 or 589 – 353 = 236

BIDMAS

This is the order of operations. Brackets and indices (formerly orders – also known as powers or roots) are done first; then division and multiplication followed by addition and subtraction.

This is covered at the top end of primary and, as its name suggests, is not just linked to addition and subtraction.